A hundred years to correctly name the fish

On the morning of Friday, August 6, 1852, Alfred Russell Wallace was called to the deck of the Helen brig. The ship was somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, and Wallace was at sea for 26 days. He was no stranger to difficulties. The previous four years he spent in the Amazon jungle, exploring uncharted territories and collecting a collection of species for himself and for English museums. The hold was filled with its precious species, many of which were new to science and could not be replaced. The 29-year-old naturalist, a native of Wales, even managed to carry several living representatives of the species - on board were parrots, ordinary and long-tailed, several monkeys and a wild forest dog.

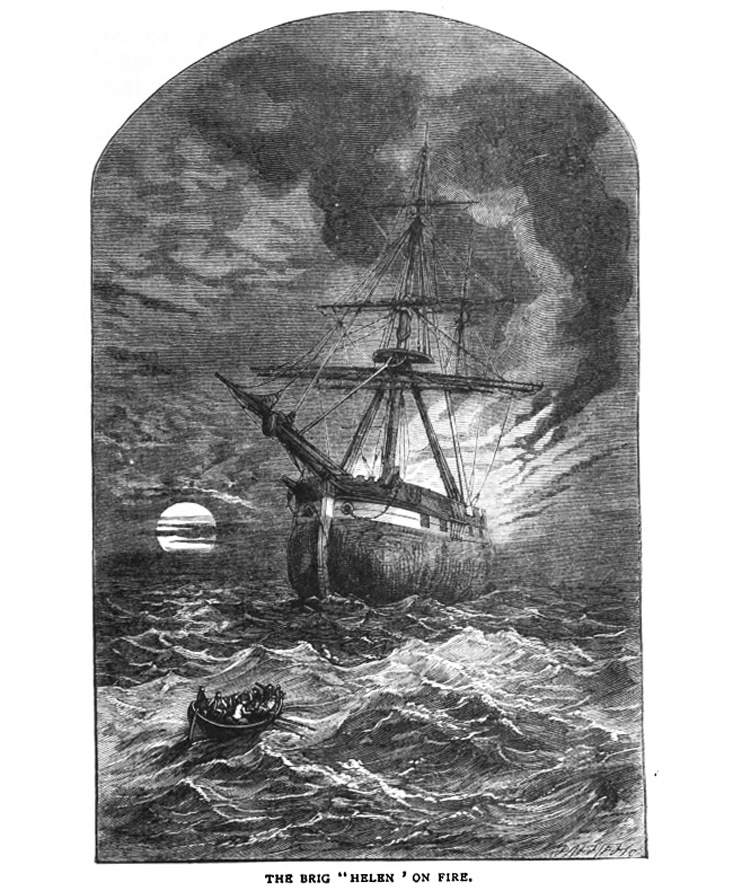

The captain said to Wallace: “I'm afraid the fire is on board. Go see.

Ten months before, in the wilds of the jungle, Wallace had caught a fever that almost killed him. He was still unwell, standing next to Captain Turner on the Helen deck and looking at the smoke rising from his cockpit. The crew violently poured water into the hold of buckets, but the fire was unstoppable, and it already swept the entire ship. The captain assembled the chronometer, sextant, compass, and nautical charts, and the team began to prepare rescue boats: a boat and a captain geek .

“I picked up a small tin box with several shirts,” Wallace later wrote in a letter to his friend, the botanist Richard Spruce , “and put my sketches of fish and palm trees there, which successfully caught my arm.”

The boats quickly loaded with provisions: “Two barrels of dry biscuits, a barrel of water, raw pork and ham, canned meat and vegetables, wine.” Then people climbed aboard. Grasping the rope to get down on the boat, Wallace slipped, skinned his hands and fell to the bottom of the boat. After some time, Helen went to the bottom of the Atlantic, taking with it an unknown variety of new species collected by Wallace [Wallace, AR: My Life: A and Chinman, London (1905)].

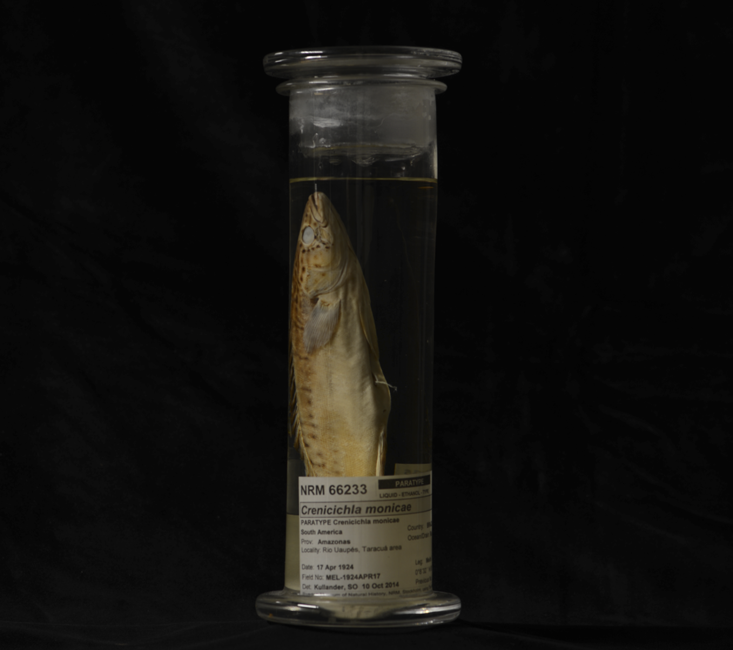

As a result, in September 2015, Sven Kullander, ichthyologist of the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm, gave the name to one of the undescribed species - characteristic colored fish. Wallace added this species to his collection in the Amazon in 1852. Cullander gave her the scientific name Crenicichla monicae .

“Crenicichla monicae belongs to the pike-cichlid group [pike cichlid],” says Cullander. The entire genus contains almost 100 known species distributed throughout the tropics and in the south of South America east of the Andes. "Pike-cichlids are elongated, and most of them have a sharp muzzle and a large maw, which reflects their predatory habits."

The fish has a long, spiny dorsal fin, running along almost the whole body, growing to 25 cm in length. Above the lateral line its long and narrow body is dotted with characteristic black spots. The descriptive work of Cullander, published in the journal Copeia, is entitled: “Wallace pike-cichlid gets its name after 160 years: a new type of cichlid from the Upper Rio Negro in Brazil” [Kullander, SA & Varella, HR A new species of cichlid fish (Teleostei: Cichlidae) from the Upper Rio Negro in Brazil. Copeia 103, 512-519 (2015)].

The Rio Negru, the main tributary of the Amazon, is a dark river, starting in southern Colombia and penetrating the jungle to the southeast. In Manaus, Rio Negru and Amazon are found. Wallace collected his fish upstream, in fast-moving areas of Rio Negro, shortly before 1852. At least one member of the species C. monicae was in the Helen hold when she sank, says Cullander. He knows this because of the pencil drawing made by Wallace after he caught the fish. He worked as a topographer and trained to draw very accurately. When the ship caught fire and began to heel, Wallace grabbed his drawings of fish and palm trees and ran away from the fire. When he fell into the boat, his drawings fell with him.

Meeting place of two rivers

Kullander, a world-class cichlid expert, is over 60, has long gray hair gathered in a ponytail, and pale blue eyes. He has been studying fish for over 50 years. A research lab was assigned to him when he was still a student.

“I first tried to watch birds, but it was boring,” he says. Instead, he settled on fish. In the 1970s, Sweden had a boom in importing cichlids from Africa as aquarium fish. Suddenly, more and more species began to appear, some of them of unusual forms. As a teenager, Cullander seized the opportunity and became an avid aquarist, and contained aquariums filled with exotic fish. “I tended toward neotropic forms; however, I was familiar with all the literature and I kept all the specimens of fish that fell into my hands, he says. “I actively communicated with other hobbyists and scholars and skipped school as often as possible.”

He wrote his first scientific papers without a supervisor, even before graduation. Finally, while working on his diploma, he had a manager — Bo Fernholm — then he was the only fish classification specialist in Sweden. Cullander gave names to more than 100 new species of cichlids. According to him, there are more than 2,000 known species of cichlids living in Asia, Africa, and North, Central and South America. Among other diagnostic criteria, ichthyologists identify new types of cichlids by the small differences of pharyngeal teeth - two plates in the pharynx covered with spikes, designed for grinding food.

Charles Darwin published his work "The Origin of Species" in 1859, but he was not alone in the theory of evolution. He worked with people like Wallace, a quiet, spectacled man who first developed some of the fundamental theories of biogeography . It was Wallace who intuitively understood the importance of geographical isolation of organisms in the process of speciation, and shared these ideas in correspondence with Darwin. For years, Wallace studied the lost parts of the Amazonian jungle, and collected species such as C. monicae. Later he spent some time on the Malay Archipelago, where he marked the " Wallace Line " - a theoretical border that runs from south to north through Indonesia, between Borneo and Sulawesi , and then turning to the northeast past the Philippines. From different sides of the line there are completely different types: Australian to the east, and Asian to the west. Where there is a barrier between two ecological zones, there is nothing but a narrow channel of water. With very few exceptions, species are found either on one or the other side of the line. Sometimes, as in the Wallace region, for example, the distinction is not so obvious.

In 1852, Wallace and other people sat in rescue boats in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and watched the flames rage on the deck and on the sails, absorbing what was left of Helen. “Shortly after,” he wrote, “because of the overturning of the vessel, the mast broke off from him and fell overboard, then quickly burned out the deck, the metal parts on the sides were red hot, and the last bowsprit disappeared, having burned off at the bottom”.

The night has come. The people in the boat remained close to the burning vessel, while the flames illuminated the black waters. At night, "Helen" turned over in the waves - there was a loud hiss when the cargo burned and turned into a liquid mass. Wallace was calm; he prepared to die. While the fire hissed in contact with the ocean, he sat in a boat and thought about lost samples: a forest dog, cans of fish, insects and parrots, three hairy monkeys. “I spent a lot of effort trying to get and pack a whole 15 meter long sheet of the magnificent Oredoxia regia palm tree, which I hoped would be a good example in the botanical room of the British Museum.”

He looked at his hands, skinned and aching from the rope, and counted his samples. “I carried with me my entire private collection of insects and birds from the time I left Par ,” he wrote, “and consisted of hundreds of new and beautiful species that I naively hoped would make my collection of American species one of the best in Europe. "

All this was gone, but Wallace's illustrations survived. As a result, they became part of the collection of the Museum of Natural History in London. In 2002, they were published under the name "Rio Negru Fish". Figure 194 is a black and white pencil drawing with many details, depicting Crenicichla monicae, with its long dorsal fin. The mouth is slightly open, and the upper part of the body is dotted with dark dots. This fish, as Wallace noted, had a characteristic red color. With a dark crimson stripe on the sides, and even her eyes were orange-red.

And in the intervening years, most of the other cichlids from Wallace's drawings were identified — at least to the genus, and often to the species. Many of the fish he painted were known even before he caught them. They were described in the 1840 monograph of the Austrian ichthyologist Johann Jacob Heckel , made on the basis of the collection collected by his countryman Johann Natterer, who participated in the expedition to Brazil from 1817. He returned to Vienna almost 20 years later with a huge collection of samples. Other species remained unknown. In 1989, Cullander described Acaronia vultuosa, another species painted by Wallace on the Amazon. Several species waited even longer - like the fish in Figure 194.

In 1923, a group of Swedish biologists traveled to some of the places where Wallace was 70 years before. These were three friends: Douglas Melin, Arthur Vilars and Abraham Roman. Melin and Roman were biologists and Vilars was an engineer and their assistant.

From Manaus they climbed north along the Rio Negru. In those places, the river was a gathering of channels flowing in one direction. Where the Vaupes River meets the Rio Negru, they walked along the Vaupes River, repeating sharp turns of the fast brown river, which became more tortuous and narrow with each kilometer. On the way, they collected representatives of species. But by mid-1924 the situation had changed. Roman left for Sweden in April. Vilars by June died of fever.

Then Melin returned to Manaus, where he sent the collected copies home, and then went on a solo expedition to Peru. In general, the biologist has collected thousands of species - frogs, cuttlefish, jumping spiders, and many botanical specimens. In April 1924, Merlin and Vilars found several specimens of characteristic colored red fish with dark spots in the Rio Negro basin near Tarakua. It was the same fish that Alfred Russell Wallace found, and which then sank into the ocean before his eyes. As a result, he said, all the specimens collected on the expedition were sent to the Swedish Museum of Natural History.

"In general, the collection of fish from Melin was small," - he says. It consisted of 130 cans, each of which contained one or several alcohol samples. “Today, when people go on expeditions, they bring thousands of species with them,” says Cullander.

Copies of C. monicae found by Melin were not identified in Stockholm. Red fish scales slowly turned pink, and then - pale blue. Eyes become dull and opaque. The sample tissue gradually decomposed. In the 1950s, ichthyologist Otto Schneidler visited a collection in Stockholm, saw samples and took them to the Bavarian zoological collection in Munich, where he worked as a curator. There they were again stored for decades without identification. In the 1990s, Cullander found these samples, still stored in Munich.

“I found these spotted fishes, and realized that it must be something new,” he says. He took two copies back to Stockholm, leaving the third in place, because he could no longer see the color. The spotty coloring of the upper body and the long fin of the fish caught by Melin and Wallace is unique among cichlids. Of the few specimens available, says Culllander, these marks are visible only in females.

“Most of the fish of the genus crenicichla looks almost the same. The distinctive coloring of Crenicichla monicae females clearly points to Wallace's drawings and allowed us to compare this fish with a spotty specimen from the Melina collection. ” Compared to its close relatives, its long dorsal fin has an extra needle. Pharyngeal teeth differ significantly. And, “unlike most pike-tsikhlidov,” says Kullander, “whose scales feel rough because of small thorns, Crenicichla monicae is one of three species of this genus with smooth scales.”

After Wallace got this fish more than 160 years ago, and then lost it - and almost a hundred years after Melin caught it again in Tarakou - she acquired a name. Since Cullander described the fish, researchers have found other lost species, also collected by Melin during their time on the Amazon. In January 2016, biologists at Auburn University, Milton Tan and Jonathan Armbrewster, gave the name to a new species of mail catfish , according to the single specimen found by Melin in the Rio Negro basin. Hypancistrus phantasma is a pale, wide catfish, with a small, low-lying maw and wedge-shaped body. Phantasma means phantom. Like Wallace's pike-cichlid, she waited in the bank for almost a hundred years. Melin and Vilars caught a copy of this species at Rio Negru on February 14, 1924 - but since then it has not been seen again.

In 1924, he lived, clinging to the bottom of the river in the depths of fast waters. Perhaps he now lives in such places - a phantom fish, like a ghost. Perhaps there are other phantom fish swimming in the banks in Stockholm or somewhere else. Over the years, specimens have become increasingly paler, slowly losing colors and a characteristic color that once distinguished them from other species.

Christopher Kemp is a scientist, author of the book Floating Gold: Natural (and Unnatural) History of Ambergris [Floating Gold: A Natural (and Unnatural) History of Ambergris].

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/410209/