The reality of color is in the process of its perception.

Arguments for a new definition of color

Philosophers have a bad reputation of people questioning recognized facts. What can be more confident than that the color of the cloudless sky in summer afternoon is blue? However, we can think: is it blue for birds flying in it, whose eyes are different from ours? And if you take some blue object - for example, the UN flag - and place a part of it in the shadow, and a part in the sun, then the first part will be darker. You can ask the question: what then is the true color of the flag? The way colors look is influenced by the lighting and movement of objects around them. Does this mean that true colors change?

All these questions indicate that colors, which at first glance are permanent, are subjective and changeable. Color is one of the old mysteries of philosophy, it questions the truth of our sensory perception of the world and provokes concern about the metaphysical compatibility of the scientific, perceptual and generally accepted idea of the world. Most philosophers have argued whether colors are real or not, whether this is a physical phenomenon or a psychological one. A more difficult task is to build a theory of how color can be an obstacle in the transition from understanding the physical to the psychological.

I can say that colors are not properties of objects (such as the UN flag) or the atmosphere (that is, the sky), but are processes of perception — an interaction involving psychological subjects and physical objects. From my point of view, colors are not properties of things, but the way objects appear before us, and at the same time the way we perceive certain types of objects. Such a definition of color opens the view on the very nature of consciousness.

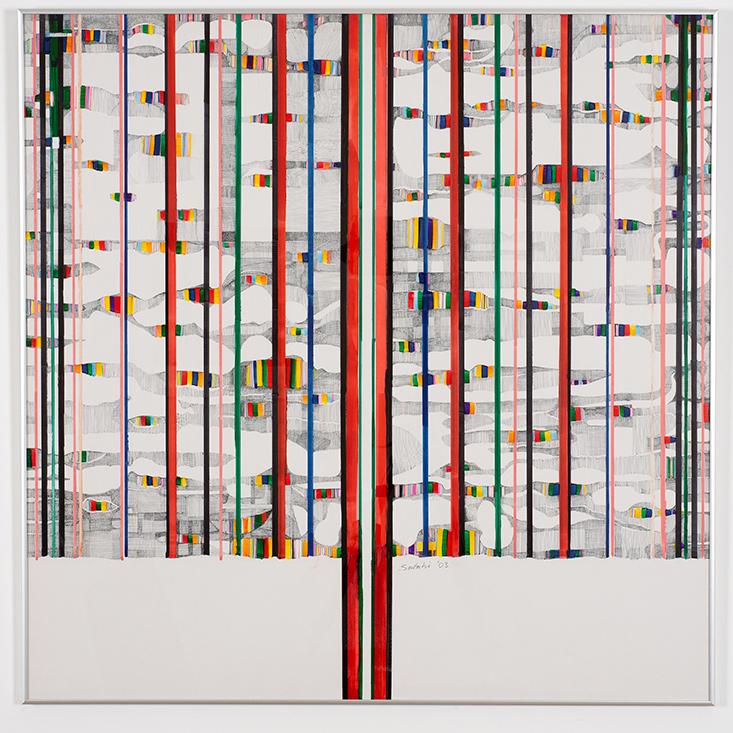

Live color. In this picture, “The Tree,” by Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi, dynamic and wavy sequences of black and white create colored vertical lines. The author of the article chose this picture for the cover of her book “External Color”, because, as she says, “I like to think that it symbolizes the appearance of color in the world due to constant interactions of perceiving subjects and perceived objects”.

Color puzzle

For philosophers of the ancient world, in particular in Greece and India, the variability of the experience of perception of reality, which varies from time to time and from person to person, was the cause of concerns about the fact that our eyes cannot be called reliable witnesses of the world around us. Such variability suggests that the experience of perception is determined not only by the things we observe, but also by our own mind. And yet, until the scientific revolution, colors were not a problem. Discussions of the philosophy of color usually originate from the 17th century, when Galileo, Descartes, Locke, or Newton began to tell us that the perceived, or "secondary" properties of objects — color, taste, smell, sound — do not belong to the physical world as we do. it seems.

In the treatise "The Assistant Workshop Master " of 1623, in the first bible of scientific methods and descriptions of using mathematics to understand the world, Galileo writes: "I don’t think that to excite tastes, smells and sounds from external bodies in us requires something other than , forms, quantities and their rapid or slow movement; I believe that if ears, tongues and noses were selected, then forms, quantities and movements would remain, and smells, sounds and tastes would disappear ”[Galileo, G. The Assayer in Drake, S. Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, New York, NY (1957)].

Modern science, coming from the XVII century, gives us a description of material objects, radically different from our usual sensory perception. Galileo says that the world contains “bodies” with properties like size, shape and movement, regardless of whether someone feels them or not. Measuring and describing things in terms of these "basic" properties, science promises to give us knowledge of the objective world, independent of the human perception that distorts it. Science can explain how molecules emitted into the air by sage can stimulate my nose, or how its petals can reflect light and appear blue-violet to my eye. But the smell and color - their conscious sensory perception - do not participate in this explanation.

Today, the problem of color is considered to be ontological - that is, it deals with what actually exists in the Universe. From a scientific point of view, it is customary to say that the only properties of objects that are indisputably existing are the properties described by physical science. For Galileo, these were sizes, shapes, quantities, and movements; for today's physicists, there are less tangible properties like electric charge. This excludes from the fundamental ontology any qualitative properties like colors known to us only thanks to our senses. But if we exclude colors, how to deal with their obvious manifestations as properties of everyday objects? Either we say that our senses deceive us, forcing us to believe that external objects are colored, although in fact there are no colors, or we are trying to find some kind of color assessment that is compatible with scientific ontology and puts them on a par with material objects.

The view described by Galileo became known as subjectivism or anti-realism . The problem is that the perception of color gives us an erroneous view of the world, and that people become victims of a systematically manifested illusion, perceiving external objects as colored. In 1988, the philosopher K. L. Hardin again turned to the view of Galileo in his remarkable work " Color for Philosophers " [Hardin, CL Color for Philosophers: Unweaving the Rainbow Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. Indianapolis, IN (1988)]. He based his assertions on the “theory of the competitive process” put forward by psychologists Leo Hörwich and Dorothea Jameson, explaining the appearance of colors through brain coding of color signals from the retina. Hardin argued that the most adequate description of the color should be neurological. In other words, colored objects do not exist outside of consciousness, in physical reality, but are only an artificial construction created by the brain.

Other philosophers accepted the challenge of finding the place of these mysterious color properties in the material world. Color realism is of different kinds. One suggestion is to define color as a kind of physical property of an object, such as “spectral surface reflection” (the predisposition of surfaces is preferable to absorb and reflect light of different wavelengths). This is the most serious attempt to preserve the generally accepted idea that colors belong to everyday things that exist in the world - for example, the sky is just blue. The main difficulty with this assumption is to compare it with our knowledge of the subjective perception of color, for example, with the changeability of the perceived color when the observer or context changes.

In this photo of the Blue Mountains near Sydney, Australia, as the hills recede into the distance, they look more and more blue and their color becomes less saturated. Psychologists refer to this color as a distance signal indicating a visible change in the size of the hills. From the point of view of the author of the article, the photograph illustrates how perception affects color: “We perceive the distance to the hills through blueness”.

Color duplicity

The problem with these sentences of realism and anti-realism is that they both focus only on the objective or subjective aspects of color. An alternative position can be described as "relationism." Colors are analyzed as real properties of objects, however, depending on the observer. Such an approach is noticeable in the science of the 17th century (in particular, in John Locke's essay " An Essay on Human Understanding "), and is reflected in the idea that colors are the susceptibility of objects to appear in a certain way. Interestingly, this relational assumption coincides with some current ideas that exist in science about color perception. Scientists-visiologists Rainer Mausfeld, Reynard Niederi and K. Dieter Heyer wrote that “the concept of human color vision includes both a subjective component associated with the phenomenon of perception and an objective one. It seems to us that this barely perceptible conflict is a necessary ingredient of color perception research ”[Mausfeld, RJ, Niederée, RM, & Heyer, KD]. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 15, 47–48 (1992)].

And a little further in the same work, they call this property “duplicity” of color: color indicates us to the world of objects, and at the same time draws us into the study of the topic of perception. This is a common trend in scientific works on color vision, and this duplicity of color always seemed to me awfully attractive.

An influential textbook by psychologist-perceptologist Stephen Palmer says that color cannot be reduced either to visual perception or to the properties of objects or light. Palmer writes that instead “color is best understood as the result of the complex interaction of the physical light that is in the environment and our visual nervous system” [Palmer, SE Vision Science: Photons to Phenomenology MIT Press (1999)].

In fact, I believe that color is not a property of the mind (visual perception), objects or light, but the perceptual process is an interaction in which all three of these concepts are involved. According to this theory, which I call the color adverb, colors are not a property of things, as it seems at first. No, colors are how external stimuli affect certain individuals, and at the same time, how individuals perceive certain stimuli. “Adverbiality” occurs because colors are considered a property of processes, not things. Therefore, instead of treating color names as adjectives (describing objects), we should treat them as adverbs (describing actions). I eat fast, go gracefully, and on a good day I see the sky blue!

Physicists often describe the blue color of the sky through Rayleigh scattering , the fact that short wavelengths of visible light are scattered by the Earth’s atmosphere more actively than long ones, so diffused blue light comes to us from all parts of the sky when the Sun is high and there are no clouds in the sky. But we should not be tempted to say that the blueness of the sky is just a property of diffusing light. No blueness exists until the light interacts with its perceiving subjects who have photoreceptors that react differently to short and long wavelengths.

Therefore, it will be more accurate to say that the sky is not blue, but we see it blue.

Outside our heads

For the "adverb", there is neither the color of objects, nor the color in the head. Color is a property of the process of perception. Since color cannot be reduced to either physics or psychology, we still have blue sky, which is neither internal nor external, but something between these concepts.

This idea affects the understanding of conscious perception. We are accustomed to think of conscious perception as something like a sequence of sounds and images passing in front of us on our internal projection screen. It is from this concept that the philosopher Alva Noe wants to depart. In his 2009 book Out of Our Heads, Out, Noe states that consciousness is not limited to the brain, but somewhere between the mind and the physical environment, and that consciousness needs to be studied in terms of actions [Noë, A Out of Our Heads Hill and Wang, New Haven, CT (2009)]. By themselves, these ideas are puzzling. But if we take the example of visual perception, then the color adverb is a way to understand the consciousness that is “outside the head.” According to the adverbiality, color perception arises from our interaction with the world, and it would not exist without contact with the environment. Our inner mental life depends on the outer context.

Mazviita Hirimuta - Assistant Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Pittsburgh, author of the book Beyond Color

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/410711/