"Modern" dining philosophers in C ++ through actors and CSP

Some time ago, a link to the article "Modern dining philosophers" spread over resources like Reddit and HackerNews. The article is interesting, it shows several solutions to this well-known problem, implemented in modern C ++ using the task-based approach. If someone has not read this article, then it makes sense to spend time and read it.

However, I cannot say that the solutions presented in the article seemed simple and clear to me. This is probably due to the use of Tasks. Too many of them are created and dispatched by various dispatchers / serializers. So it is not always clear where, when and what tasks are performed.

At the same time, the task-based approach is not the only one possible to solve such problems. Why not see how the task of the "dining philosophers" is solved through the models of actors and CSP?

Therefore, I tried to look at and implemented several solutions to this problem both with the use of Actors and with the use of CSP. The code for these solutions can be found in the BitBucket repository . And under the cut explanations and explanations, so who cares, you are welcome under the cat.

A few common words

I didn’t have the goal of exactly repeating the solutions shown in the very article "Modern dining philosophers" , especially since I fundamentally dislike one important thing: in fact, the "philosopher" does not do anything in those decisions. He only says “I want to eat,” and then either someone magically provides forks to him, or he says “now it won't work out”.

It is clear why the author resorted to this behavior: it allows you to use the same implementation of the "philosopher" in conjunction with different implementations of the "protocols". However, it seems to me personally that it is more interesting when exactly the “philosopher” tries to take one fork first, then the other. And when the "philosopher" is forced to handle unsuccessful attempts to seize the plug.

It is such an implementation of the task of the "dining philosophers" that I tried to do. In this case, some solutions used the same approaches as in the above-mentioned article (for example, implemented by the ForkLevelPhilosopherProtocol and WaiterFair protocols).

I built my decisions on the basis of SObjectizer , which would hardly surprise those who read my articles before. If someone has not yet heard about SObjectizer, then in a nutshell: this is one of the few living and developing OpenSource "action frameworks" for C ++ (among others, CAF and QP / C ++ can also be mentioned). I hope that the examples given with my comments will be clear enough even for those unfamiliar with SObjectizer. If not, I will be happy to answer questions in the comments.

Actor based solutions

The discussion of implemented solutions will begin with those made on the basis of the Actors. First, consider the implementation of the Edsger Dijkstra solution, then move on to several other solutions and see how the behavior of each of the solutions differs.

Dijkstra's decision

Edsger Dijkstra, not only did he formulate the task of “dining filophos” (formulated using forks and spaghetti voiced by Tony Hoar), he also suggested a very simple and beautiful solution. Namely: philosophers should seize the forks only in the order of increasing numbers of the forks, and if the philosopher managed to take the first fork, then he would not let go of it until he received the second fork.

For example, if a philosopher needs to use plugs with numbers 5 and 6, the philosopher must first take plug number 5. Only after that he can take plug number 6. Thus, if forks with smaller numbers lie to the left of philosophers, then the philosopher must first take the left fork and only then can it take the right fork.

The last philosopher on the list, who has to deal with forks for numbers (N-1) and 0, does the opposite: he first takes the right fork with the number 0, and then the left fork with the number (N-1).

To implement this approach, two types of actors are required: one for forks, the second for philosophers. If the philosopher wants to eat, he sends a message to the corresponding actor-fork to seize the fork, and the actor-fork responds with a response message.

The implementation code for this approach can be seen here .

Messages

Before talking about the actors, you need to look at the messages that the actors will exchange:

struct take_t { const so_5::mbox_t m_who; std::size_t m_philosopher_index; }; struct taken_t : public so_5::signal_t {}; struct put_t : public so_5::signal_t {}; When a philosopher actor wants to take a fork, he sends the take_t message to the fork take_t , and the actor-fork responds with the message taken_t . When the philosopher actor finishes eating and wants to put the forks back on the table, he sends the messages put_t to the forks put_t .

In the take_t message, the take_t field indicates the mailbox (aka mbox) of the actor-philosopher. A reply message taken_t should be sent to this taken_t . The second field from take_t is not used in this example, we will need it when we get to the waiter_with_queue and waiter_with_timestamps implementations.

Actor Fork

Now we can look at what the actor-plug is. Here is his code:

class fork_t final : public so_5::agent_t { public : fork_t( context_t ctx ) : so_5::agent_t{ std::move(ctx) } {} void so_define_agent() override { // Начальным должно быть состояние 'free'. this >>= st_free; // В состоянии 'free' обрабатывается только одно сообщение. st_free .event( [this]( mhood_t<take_t> cmd ) { this >>= st_taken; so_5::send< taken_t >( cmd->m_who ); } ); // В состоянии 'taken' обрабатываются два сообщения. st_taken .event( [this]( mhood_t<take_t> cmd ) { // Философу придется подождать в очереди. m_queue.push( cmd->m_who ); } ) .event( [this]( mhood_t<put_t> ) { if( m_queue.empty() ) // Вилка сейчас никому не нужна. this >>= st_free; else { // Вилка должна достаться первому из очереди. const auto who = m_queue.front(); m_queue.pop(); so_5::send< taken_t >( who ); } } ); } private : // Определение состояний для актора. const state_t st_free{ this, "free" }; const state_t st_taken{ this, "taken" }; // Очередь ждущих философов. std::queue< so_5::mbox_t > m_queue; }; Each actor in SObjectizer should be derived from the base class agent_t . What we see here is for the fork_t type.

In the fork_t class, the so_define_agent() method is so_define_agent() . This is a special method, it is automatically called by SObjectizer when registering a new agent. In the so_define_agent() method, the so_define_agent() is "configured" to work in SObjectizer: the starting state changes, the necessary messages are subscribed to.

Each actor in a SObjectizer is a state machine with states (even if the actor uses only one default state). Here the fork_t actor has two states: free and taken . When the actor is free , the plug can be "captured" by the philosopher. And after the fork is fork_t actor should go into the state of taken . Inside the fork_t class fork_t states are represented by instances of st_free and st_taken special type state_t .

States allow you to process incoming messages in different ways. For example, in the free state, the agent responds only to take_t and this reaction is very simple: the state of the actor changes and the response taken_t :

st_free .event( [this]( mhood_t<take_t> cmd ) { this >>= st_taken; so_5::send< taken_t >( cmd->m_who ); } ); While all other messages, including put_t in the free state, are simply ignored.

In the state taken, the actor handles two messages, and even the take_t message it processes differently:

st_taken .event( [this]( mhood_t<take_t> cmd ) { m_queue.push( cmd->m_who ); } ) .event( [this]( mhood_t<put_t> ) { if( m_queue.empty() ) this >>= st_free; else { const auto who = m_queue.front(); m_queue.pop(); so_5::send< taken_t >( who ); } } ); Here the handler for put_t most interesting: if the queue of waiting philosophers is empty, then we can return to free , but if not empty, then the first one should be sent taken_t .

Actor-philosopher

The code of the actor-philosopher is much more extensive, so I will not give it here in full. We will discuss only the most significant fragments.

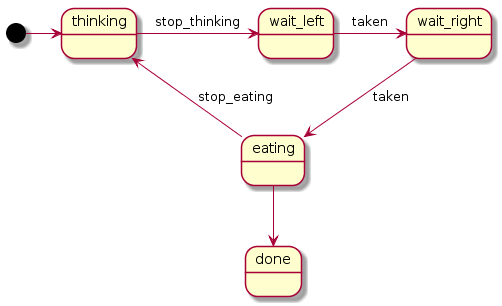

The actor-philosopher has several more states:

state_t st_thinking{ this, "thinking.normal" }; state_t st_wait_left{ this, "wait_left" }; state_t st_wait_right{ this, "wait_right" }; state_t st_eating{ this, "eating" }; state_t st_done{ this, "done" }; The actor starts his work in the state of thinking , then switches to wait_left , then to wait_right , then to eating . From eating the actor can return to thinking or can go to done if the philosopher ate everything he should have.

The state diagram for the actor-philosopher can be represented as follows:

The logic of the behavior of the actor is described in the implementation of its so_define_agent() method:

void so_define_agent() override { // В состоянии thinking реагируем только на сигнал stop_thinking. st_thinking .event( [=]( mhood_t<stop_thinking_t> ) { // Пытаемся взять левую вилку. this >>= st_wait_left; so_5::send< take_t >( m_left_fork, so_direct_mbox(), m_index ); } ); // Когда ждем левую вилку реагируем только на taken. st_wait_left .event( [=]( mhood_t<taken_t> ) { // У нас есть левая вилка. Пробуем взять правую. this >>= st_wait_right; so_5::send< take_t >( m_right_fork, so_direct_mbox(), m_index ); } ); // Пока ждем правую вилку, реагируем только на taken. st_wait_right .event( [=]( mhood_t<taken_t> ) { // У нас обе вилки, можно поесть. this >>= st_eating; } ); // Пока едим реагируем только на stop_eating. st_eating // 'stop_eating' должен быть отослан как только входим в 'eating'. .on_enter( [=] { so_5::send_delayed< stop_eating_t >( *this, eat_pause() ); } ) .event( [=]( mhood_t<stop_eating_t> ) { // Обе вилки нужно вернуть на стол. so_5::send< put_t >( m_right_fork ); so_5::send< put_t >( m_left_fork ); // На шаг ближе к финалу. ++m_meals_eaten; if( m_meals_count == m_meals_eaten ) this >>= st_done; // Съели все, что могли, пора завершаться. else think(); } ); st_done .on_enter( [=] { // Сообщаем о том, что мы закончили. completion_watcher_t::done( so_environment(), m_index ); } ); } Perhaps the only point on which it should stop especially is the approach to imitating the processes of "thinking" and "food." There is no this_thread::sleep_for or any other way of blocking the current working thread in the actor code. Instead, deferred messages are used. For example, when the actor enters the eating state, it sends to itself a pending message stop_eating_t . This message is given to the SObjectizer timer, and the timer delivers the message to the actor when the time comes.

The use of deferred messages allows you to run all the actors in the context of a single working thread. Roughly speaking, one thread reads from some message queue and pulls the handler of the next message from the corresponding receiving actor. More on working contexts for actors will be discussed below.

results

The results of this implementation may look like this (small fragment):

Socrates: tttttttttttLRRRRRRRRRRRRRREEEEEEEttttttttLRRRRRRRRRRRRRREEEEEEEEEEEEE Plato: ttttttttttEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttRRRRRREEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttLLL Aristotle: ttttEEEEEtttttttttttLLLLLLRRRREEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttttLLEEEEEEEEEEEEE Descartes: tttttLLLLRRRRRRRREEEEEEEEEEEEEtttLLLLLLLLLRRRRREEEEEEttttttttttLLLLLL Spinoza: ttttEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttLLLRRRREEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttRRRREEEEEEtt Kant: ttttttttttLLLLLLLRREEEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttLLLEEEEEEEEEEEEEEtttttttt Schopenhauer: ttttttEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttLLLLLLLLLEEEEEEEEEttttttttLLLLLLLLLLRRRRRRRR Nietzsche: tttttttttLLLLLLLLLLEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttLLLEEEEEEEEEttttttttRRRRRRRRE Wittgenstein: ttttEEEEEEEEEEtttttLLLLLLLLLLLLLEEEEEEEEEttttttttttttRRRREEEEEEEEEEEt Heidegger: tttttttttttLLLEEEEEEEEEEEEEEtttttttLLLLLLREEEEEEEEEEEEEEEtttLLLLLLLLR Sartre: tttEEEEEEEEEttttLLLLLLLLLLLLRRRRREEEEEEEEEtttttttLLLLLLLLRRRRRRRRRRRR Read this as follows:

tmeans that the philosopher "reflects";Lmeans that the philosopher is waiting for the capture of the left fork (is in the wait_left state);Rmeans that the philosopher is waiting for the capture of the right fork (is in the wait_right state);Emeans that the philosopher is "eating."

We can see that Socrates can take the plug on the left only after Sartre gives it away. Then Socrates will wait for Plato to release the right fork. Only then can Socrates eat.

A simple decision without an arbitrator (waiter)

If we analyze the result of the work of Dijkstra’s solution, we will see that philosophers spend a lot of time waiting for the forks to be captured. What is not good, because This time can also be spent on meditation. Not for nothing is the opinion that if you think on an empty stomach, you can get much more interesting and unexpected results;)

Let's look at the simplest solution, in which the philosopher returns the first fork seized if he cannot capture the second one (in the Modern Dining philosophers article mentioned above, this solution is implemented by ForkLevelPhilosopherProtocol).

The source code of this implementation can be seen here , and the code of the corresponding actor-philosopher is here .

Messages

This solution uses almost the same set of messages:

struct take_t { const so_5::mbox_t m_who; std::size_t m_philosopher_index; }; struct busy_t : public so_5::signal_t {}; struct taken_t : public so_5::signal_t {}; struct put_t : public so_5::signal_t {}; The only difference is the presence of the busy_t signal. This signal actor-fork sends in response to the actor-philosopher if the plug is already captured by another philosopher.

Actor Fork

Actor-fork in this solution is even easier than in the decision Dijkstra:

class fork_t final : public so_5::agent_t { public : fork_t( context_t ctx ) : so_5::agent_t( ctx ) { this >>= st_free; st_free.event( [this]( mhood_t<take_t> cmd ) { this >>= st_taken; so_5::send< taken_t >( cmd->m_who ); } ); st_taken.event( []( mhood_t<take_t> cmd ) { so_5::send< busy_t >( cmd->m_who ); } ) .just_switch_to< put_t >( st_free ); } private : const state_t st_free{ this }; const state_t st_taken{ this }; }; We do not even need to keep the waiting line of philosophers here.

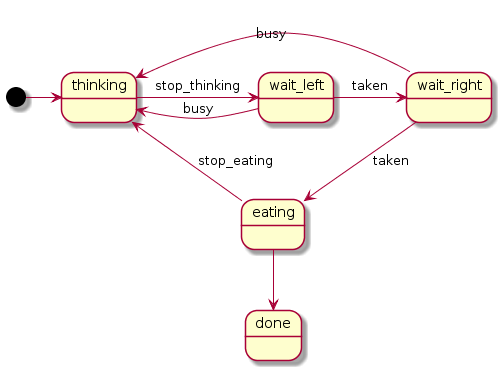

Actor-philosopher

The actor-philosopher in this implementation is similar to that of Dijkstra’s decision, but here the actor-philosopher also has to process busy_t , so the state diagram looks like this:

Similarly, the entire logic of the actor-philosopher is defined in so_define_agent() :

void so_define_agent() override { st_thinking .event< stop_thinking_t >( [=] { this >>= st_wait_left; so_5::send< take_t >( m_left_fork, so_direct_mbox(), m_index ); } ); st_wait_left .event< taken_t >( [=] { this >>= st_wait_right; so_5::send< take_t >( m_right_fork, so_direct_mbox(), m_index ); } ) .event< busy_t >( [=] { think( st_hungry_thinking ); } ); st_wait_right .event< taken_t >( [=] { this >>= st_eating; } ) .event< busy_t >( [=] { so_5::send< put_t >( m_left_fork ); think( st_hungry_thinking ); } ); st_eating .on_enter( [=] { so_5::send_delayed< stop_eating_t >( *this, eat_pause() ); } ) .event< stop_eating_t >( [=] { so_5::send< put_t >( m_right_fork ); so_5::send< put_t >( m_left_fork ); ++m_meals_eaten; if( m_meals_count == m_meals_eaten ) this >>= st_done; else think( st_normal_thinking ); } ); st_done .on_enter( [=] { completion_watcher_t::done( so_environment(), m_index ); } ); } In general, this is practically the same code as in Dijkstra’s solution, except that a couple of handlers for busy_t .

results

The results of the work look different:

Socrates: tttttttttL..R.....EEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttR...LL..EEEEEEEttEEEEEE Plato: ttttEEEEEEEEEEEttttttL.....L..EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttL....L.... Aristotle: ttttttttttttL..LR.EEEEEEtttttttttttL..L....L....R.....EEEEEEEEE Descartes: ttttttttttEEEEEEEEttttttttttttEEEEEEEEttttEEEEEEEEEEEttttttL..L.. Spinoza: ttttttttttL.....L...EEEEEEtttttttttL.L......L....L..L...R...R...E Kant: tttttttEEEEEEEttttttttL.L.....EEEEEEEEttttttttR...R..R..EEEEEtttt Schopenhauer: tttR..R..L.....EEEEEEEttttttR.....L...EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttt Nietzsche: tttEEEEEEEEEEtttttttttEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttL....L...L..L....EEEEEEE Wittgenstein: tttttL.L..L.....RR....L.....L....L...EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEtttttttttL. Heidegger: ttttR..R......EEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttR..L...L...L..L...EEEEtttttt Sartre: tttEEEEEEEtttttttL..L...L....R.EEEEEEEtttttEEEEtttttttR.....R..R. Here we see a new symbol, which means that the actor-philosopher is in "hungry thoughts".

Even on this short fragment, one can see that there are long moments of time during which the philosopher cannot eat. This is because this solution is protected from the problem of deadlocks, but does not have protection against fasting.

Solution with a waiter and a queue

The simplest solution shown above without an arbitrator does not protect against fasting. The above-mentioned article "Modern dining philosophers" contains a solution to the problem of fasting in the form of the WaiterFair protocol. The bottom line is that an arbitrator (waiter) appears to whom philosophers turn to when they want to eat. And the waiter has a queue of applications from philosophers. And the philosopher gets the forks only if both of the forks are now free, and there is still no one in the queue of the neighbors of the philosopher who turned to the waiter.

Let's look at how the same solution might look like on actors.

The source code for this implementation can be found here .

Trick

The easiest thing would be to introduce a new set of messages through which philosophers could communicate with the waiter. But I wanted to save not only the already existing set of messages (i.e. take_t , taken_t , busy_t , put_t ). I also wanted the same actor-philosopher to be used as in the previous decision. Therefore, I needed to solve a clever puzzle: how to make the actor-philosopher communicate with the only actor-waiter, but at the same time thought that he interacts directly with the actors-forks (which are no longer in fact).

This problem was solved with the help of a simple trick: the actor-waiter creates a set of mboxes, links to which are given to actors-philosophers as references to the mboxes of the forks. At the same time, the actor-waiter subscribes to messages from all these mboxes (which is easily implemented in SObjectizer, since SObjectizer is not only / much of the Actor model, but also Pub / Sub is supported out of the box) .

In code, it looks like this:

class waiter_t final : public so_5::agent_t { public : waiter_t( context_t ctx, std::size_t forks_count ) : so_5::agent_t{ std::move(ctx) } , m_fork_states( forks_count, fork_state_t::free ) { // Нужны mbox-ы для каждой "вилки" m_fork_mboxes.reserve( forks_count ); for( std::size_t i{}; i != forks_count; ++i ) m_fork_mboxes.push_back( so_environment().create_mbox() ); } ... void so_define_agent() override { // Требуется создать подписки для каждой "вилки". for( std::size_t i{}; i != m_fork_mboxes.size(); ++i ) { // Нам нужно знать индекс вилки. Поэтому используются лямбды. // Лямбда захватывает индекс и затем отдает этот индекс в // актуальный обработчик входящего сообщения. so_subscribe( fork_mbox( i ) ) .event( [i, this]( mhood_t<take_t> cmd ) { on_take_fork( std::move(cmd), i ); } ) .event( [i, this]( mhood_t<put_t> cmd ) { on_put_fork( std::move(cmd), i ); } ); } } private : ... // Почтовые ящики для несуществующих "вилок". std::vector< so_5::mbox_t > m_fork_mboxes; Those. First, create a vector mboxes for non-existent "forks", then subscribe to each of them. Yes, so we subscribe to know which plug the request belongs to.

The real handler for the on_take_fork() incoming request is the on_take_fork() method:

void on_take_fork( mhood_t<take_t> cmd, std::size_t fork_index ) { // Используем тот факт, что у левой вилки индекс совпадает // с индексом самого философа. if( fork_index == cmd->m_philosopher_index ) handle_take_left_fork( std::move(cmd), fork_index ); else handle_take_right_fork( std::move(cmd), fork_index ); } By the way, it was here that we needed the second field from the take_t message.

So, in on_take_fork() we have the original query and the index of the fork to which the query belongs. Therefore, we can determine whether the philosopher is asking for the left or right fork. And, accordingly, we can process them in different ways (and we have to process them in different ways).

Since the philosopher always asks for the left plug first, we need to do all the necessary checks at this very moment. And we may end up in one of the following situations:

- Both forks are free and can be given to the philosopher who sent the request. In this case, we

taken_tphilosopher, and mark the right fork as reserved so that no one else can take it. - Plugs cannot be given to the philosopher. No matter why. Maybe some of them are busy right now. Or in the queue there is someone from the neighbors of the philosopher. Как бы то ни было, мы помещаем философа, приславшего запрос, в очередь, после чего отсылаем ему

busy_t.

Благодаря такой логике работы философ, получивший taken_t для левой вилки, может спокойно послать запрос take_t для правой вилки. Этот запрос будет сразу же удовлетворен, т.к. вилка уже зарезервирована для данного философа.

results

Если запустить получившееся решение, то можно увидеть что-то вроде:

Socrates: tttttttttttL....EEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttL...L...EEEEEEEEEEEEEtttttL. Plato: tttttttttttL....L..L..L...L...EEEEEEEEEEEEEtttttL.....L....L.....EEE Aristotle: tttttttttL.....EEEEEEEEEttttttttttL.....L.....EEEEEEEEEEEtttL....LL Descartes: ttEEEEEEEEEEtttttttL.L..EEEEEEEEEEEEtttL..L....L....L.....EEEEEEEEEE Spinoza: tttttttttL.....EEEEEEEEEttttttttttL.....L.....EEEEEEEEEEEtttL....LL Kant: ttEEEEEEEEEEEEEtttttttL...L.....L.....EEEEEttttL....L...L..L...EEEEE Schopenhauer: ttttL...L.....L.EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEtttttttttttL..L...L..EEEEEEEttttttt Nietzsche: tttttttttttL....L..L..L...L...L.....L....EEEEEEEEEEEEttL.....L...L.. Wittgenstein: tttttttttL....L...L....L....L...EEEEEEEttttL......L.....L.....EEEEEE Heidegger: ttttttL..L...L.....EEEEEEEEEEEEtttttL...L..L.....EEEEEEEEEEEttttttL. Sartre: ttEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttL.....L...EEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttttL.....EEEEE Можно обратить внимание на отсутствие символов R . Это потому, что не может возникнуть неудачи или ожидания на запросе правой вилки.

Еще одно решение с использованием арбитра (официанта)

В некоторых случаях предыдущее решение waiter_with_queue может показывать результаты, похожие вот на этот:

Socrates: tttttEEEEEEEEEEEEEEtttL.....LL...L....EEEEEEEEEttttttttttL....L.....EE Plato: tttttL..L..L....LL...EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttttL.....EEEEEEEEEttttttt Aristotle: tttttttttttL..L...L.....L.....L....L.....EEEEEEEEEEEEtttttttttttL....L.. Descartes: ttttttttttEEEEEEEEEEttttttL.....L....L..L.....L.....L..L...L..EEEEEEEEtt Spinoza: tttttttttttL..L...L.....L.....L....L.....L..L..L....EEEEEEEEEEtttttttttt Kant: tttttttttL....L....L...L...L....L..L...EEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttL...L......E Schopenhauer: ttttttL....L..L...L...LL...L...EEEEEtttttL....L...L.....EEEEEEEEEttttt Nietzsche: tttttL..L..L....EEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttttEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEttttttttttttL... Wittgenstein: tttEEEEEEEEEEEEtttL....L....L..EEEEEEEEEtttttL..L..L....EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE Heidegger: tttttttttL...L..EEEEEEEEttttL..L.....L...EEEEEEEEEtttL.L..L...L....L...L Sartre: ttttttttttL..L....L...L.EEEEEEEEEEEtttttL...L..L....EEEEEEEEEEtttttttttt Можно увидеть наличие достаточно длинных периодов времени, когда философы не могут поесть даже не смотря на наличие свободных вилок. Например, левая и правая вилки для Канта свободны на протяжении длительного времени, но Кант не может их взять, т.к. в очереди ожидания уже стоят его соседи. Которые ждут своих соседей. Которые ждут своих соседей и т.д.

Поэтому рассмотренная выше реализация waiter_with_queue защищает от голодания в том смысле, что рано или поздно философ поест. Это ему гарантировано. Но периоды голодания могут быть довольно долгими. И утилизация ресурсов может быть не оптимальной временами.

Дабы решить эту проблему я реализовал еще одно решение, waiter_with_timestamp (его код можно найти здесь ). Вместо очереди там используется приоритизация запросов от философов с учетом времени их голодания. Чем дольше философ голодает, тем приоритетнее его запрос.

Рассматривать код этого решения мы не будем, т.к. по большому счету главное в нем — это тот же самый трюк с набором mbox-ов для несуществующих "вилок", который мы уже обсудили в разговоре про реализацию waiter_with_queue.

Несколько деталей реализации, на которые хотелось бы обратить внимание

Есть несколько деталей в реализациях на базе Акторов, на которые хотелось бы обратить внимание, т.к. эти детали демонстрируют интересные особенности SObjectizer-а.

Рабочий контекст для акторов

В рассмотренных реализациях все основные акторы ( fork_t , philosopher_t , waiter_t ) работали на контексте одной общей рабочей нити. Что вовсе не означает, что в SObjectizer-е все акторы работают только на одной единственной нити. В SObjectizer-е можно привязывать акторов к разным контекстам, что можно увидеть, например, в коде функции run_simulation() в решении no_waiter_simple.

void run_simulation( so_5::environment_t & env, const names_holder_t & names ) { env.introduce_coop( [&]( so_5::coop_t & coop ) { coop.make_agent_with_binder< trace_maker_t >( so_5::disp::one_thread::create_private_disp( env )->binder(), names, random_pause_generator_t::trace_step() ); coop.make_agent_with_binder< completion_watcher_t >( so_5::disp::one_thread::create_private_disp( env )->binder(), names ); const auto count = names.size(); std::vector< so_5::agent_t * > forks( count, nullptr ); for( std::size_t i{}; i != count; ++i ) forks[ i ] = coop.make_agent< fork_t >(); for( std::size_t i{}; i != count; ++i ) coop.make_agent< philosopher_t >( i, forks[ i ]->so_direct_mbox(), forks[ (i + 1) % count ]->so_direct_mbox(), default_meals_count ); }); } В этой функции создаются дополнительные акторы типов trace_maker_t и completion_watcher_t . Они будут работать на отдельных рабочих контекстах. Для этого создается два экземпляра диспетчера типа one_thread и акторы привязываются к этим экземплярам диспетчеров. Что означает, что данные акторы будут работать как активные объекты : каждый будет владеть собственной рабочей нитью.

SObjectizer предоставляет набор из нескольких разных диспетчеров, которые могут использоваться прямо "из коробки". При этом разработчик может создать в своем приложении столько экземпляров диспетчеров, сколько разработчику нужно.

Но самое важное то, что в самом акторе ничего не нужно менять, чтобы заставить его работать на другом диспетчере. Скажем, мы легко можем запустить акторов fork_t на одном пуле рабочих нитей, а акторов philosopher_t на другом пуле.

void run_simulation( so_5::environment_t & env, const names_holder_t & names ) { env.introduce_coop( [&]( so_5::coop_t & coop ) { coop.make_agent_with_binder< trace_maker_t >( so_5::disp::one_thread::create_private_disp( env )->binder(), names, random_pause_generator_t::trace_step() ); coop.make_agent_with_binder< completion_watcher_t >( so_5::disp::one_thread::create_private_disp( env )->binder(), names ); const auto count = names.size(); // Параметры для настройки поведения thread_pool-диспетчера. so_5::disp::thread_pool::bind_params_t bind_params; bind_params.fifo( so_5::disp::thread_pool::fifo_t::individual ); std::vector< so_5::agent_t * > forks( count, nullptr ); // Создаем пул нитей для акторов-вилок. auto fork_disp = so_5::disp::thread_pool::create_private_disp( env, 3u // Размер пула. ); for( std::size_t i{}; i != count; ++i ) // Каждая вилка будет привязана к пулу. forks[ i ] = coop.make_agent_with_binder< fork_t >( fork_disp->binder( bind_params ) ); // Создаем пул нитей для акторов-философов. auto philosopher_disp = so_5::disp::thread_pool::create_private_disp( env, 6u // Размер пула. ); for( std::size_t i{}; i != count; ++i ) coop.make_agent_with_binder< philosopher_t >( philosopher_disp->binder( bind_params ), i, forks[ i ]->so_direct_mbox(), forks[ (i + 1) % count ]->so_direct_mbox(), default_meals_count ); }); } И при этом нам не потребовалось поменять ни строчки в классах fork_t и philosopher_t .

Трассировка смены состояний акторов

Если посмотреть в реализацию философов в упомянутой выше статье Modern dining philosophers можно легко увидеть код, относящийся к трассировке действий философа, например:

void doEat() { eventLog_.startActivity(ActivityType::eat); wait(randBetween(10, 50)); eventLog_.endActivity(ActivityType::eat); В тоже время в показанных выше реализациях на базе SObjectizer подобного кода нет. Но трассировка, тем не менее, выполняется. За счет чего?

Дело в том, что в SObjectizer-е есть специальная штука: слушатель состояний агента. Такой слушатель реализуется как наследник класса agent_state_listener_t . Когда слушатель связывается с агентом, то SObjectizer автоматически уведомляет слушателя о каждом изменении состояния агента.

Установку слушателя можно увидеть в конструкторе агентов greedy_philosopher_t и philosopher_t :

philosopher_t(...) ... { so_add_destroyable_listener( state_watcher_t::make( so_environment(), index ) ); } Здесь state_watcher_t — это и есть нужная мне реализация слушателя.

class state_watcher_t final : public so_5::agent_state_listener_t { const so_5::mbox_t m_mbox; const std::size_t m_index; state_watcher_t( so_5::mbox_t mbox, std::size_t index ); public : static auto make( so_5::environment_t & env, std::size_t index ) { return so_5::agent_state_listener_unique_ptr_t{ new state_watcher_t{ trace_maker_t::make_mbox(env), index } }; } void changed( so_5::agent_t &, const so_5::state_t & state ) override; }; Когда экземпляр state_watcher_t связан с агентом SObjectizer вызывает метод changed() при смене состояния агента. И уже внутри state_watcher_t::changed инициируются действия для трассировки действий актора-философа.

void state_watcher_t::changed( so_5::agent_t &, const so_5::state_t & state ) { const auto detect_label = []( const std::string & name ) {...}; const char state_label = detect_label( state.query_name() ); if( '?' == state_label ) return; so_5::send< trace::state_changed_t >( m_mbox, m_index, state_label ); } Решения на базе CSP

Теперь мы поговорим о реализациях, которые не используют акторов вообще. Посмотрим на те же самые решения (no_waiter_dijkstra, no_waiter_simple, waiter_with_timestamps) при реализации которых применяются std::thread и SObjectizer-овские mchain-ы (которые, по сути, есть CSP-шные каналы). Причем, подчеркну особо, в CSP-шных решениях используется тот же самый набор сообщений (все те же take_t , taken_t , busy_t , put_t ).

В CSP-подходе вместо "процессов" используются нити ОС. Поэтому каждая вилка, каждый философ и каждый официант реализуется отдельным объектом std::thread .

Решение Дейкстры

Исходный код этого решения можно увидеть здесь .

Нить для вилки

Нить для вилки в решении Дейкстры работает очень просто: цикл чтения сообщений из входного канала + обработка сообщений типа take_t и put_t . Что реализуется функцией fork_process следующего вида:

void fork_process( so_5::mchain_t fork_ch ) { // Состояние вилки: занята или нет. bool taken = false; // Очередь ждущих философов. std::queue< so_5::mbox_t > wait_queue; // Читаем и обрабатываем сообщения пока канал не закроют. so_5::receive( so_5::from( fork_ch ), [&]( so_5::mhood_t<take_t> cmd ) { if( taken ) // Вилка занята, философ должен ждать в очереди. wait_queue.push( cmd->m_who ); else { // Философ может взять вилку. taken = true; so_5::send< taken_t >( cmd->m_who ); } }, [&]( so_5::mhood_t<put_t> ) { if( wait_queue.empty() ) taken = false; // Вилка больше никому не нужна. else { // Вилку нужно отдать первому философу из очереди. const auto who = wait_queue.front(); wait_queue.pop(); so_5::send< taken_t >( who ); } } ); } У функции fork_process всего один аргумент: входной канал, который создается где-то в другом месте.

Самое интересное в fork_process — это "цикл" выборки сообщений из канала до тех пор, пока канал не будет закрыт. Этот цикл реализуется всего одним вызовом функции receive() :

so_5::receive( so_5::from( fork_ch ), [&]( so_5::mhood_t<take_t> cmd ) {...}, [&]( so_5::mhood_t<put_t> ) {...} ); В SObjectizer-е есть несколько версий функции receive() и здесь мы видим одну из них. Эта версия читает сообщения из канала пока канал не будет закрыт. Для каждого прочитанного сообщения ищется обработчик. Если обработчик найден, то он вызывается и сообщение обрабатывается. Если не найден, то сообщение просто выбрасывается.

Обработчики сообщений задаются в виде лямбда-функций. Эти лямбды выглядят как близнецы братья соответствующих обработчиков в акторе fork_t из решения на базе Акторов. Что, в принципе, не удивительно.

Нить для философа

Логика работы философа реализована в функции philosopher_process . У этой функции достаточно объемный код, поэтому мы будем разбираться с ним по частям.

oid philosopher_process( trace_maker_t & tracer, so_5::mchain_t control_ch, std::size_t philosopher_index, so_5::mbox_t left_fork, so_5::mbox_t right_fork, int meals_count ) { int meals_eaten{ 0 }; random_pause_generator_t pause_generator; // Этот канал будет использован для получения ответов от вилок. auto self_ch = so_5::create_mchain( control_ch->environment() ); while( meals_eaten < meals_count ) { tracer.thinking_started( philosopher_index, thinking_type_t::normal ); // Имитируем размышления приостанавливая нить. std::this_thread::sleep_for( pause_generator.think_pause( thinking_type_t::normal ) ); // Пытаемся взять левую вилку. tracer.take_left_attempt( philosopher_index ); so_5::send< take_t >( left_fork, self_ch->as_mbox(), philosopher_index ); // Запрос отправлен, ждем ответа. so_5::receive( so_5::from( self_ch ).handle_n( 1u ), [&]( so_5::mhood_t<taken_t> ) { // Взяли левую вилку, пытаемся взять правую. tracer.take_right_attempt( philosopher_index ); so_5::send< take_t >( right_fork, self_ch->as_mbox(), philosopher_index ); // Запрос отправлен, ждем ответа. so_5::receive( so_5::from( self_ch ).handle_n( 1u ), [&]( so_5::mhood_t<taken_t> ) { // У нас обе вилки. Можно поесть. tracer.eating_started( philosopher_index ); // Имитируем поглощение пищи приостанавливая нить. std::this_thread::sleep_for( pause_generator.eat_pause() ); // На шаг ближе к финалу. ++meals_eaten; // После еды возвращаем правую вилку. so_5::send< put_t >( right_fork ); } ); // А следом возвращаем и левую. so_5::send< put_t >( left_fork ); } ); } // Сообщаем о том, что мы закончили. tracer.philosopher_done( philosopher_index ); so_5::send< philosopher_done_t >( control_ch, philosopher_index ); } Давайте начнем с прототипа функции:

void philosopher_process( trace_maker_t & tracer, so_5::mchain_t control_ch, std::size_t philosopher_index, so_5::mbox_t left_fork, so_5::mbox_t right_fork, int meals_count ) Смысл и назначение некоторых из этих параметров придется пояснить.

Поскольку мы не используем SObjectizer-овских агентов, то у нас нет возможности снимать след работы философа через слушателя состояний агента, как это делалось в варианте на Actor-ах. Поэтому в коде философа приходится делать вот такие вставки:

tracer.thinking_started( philosopher_index, thinking_type_t::normal ); И аргумент tracer как раз является ссылкой на объект, который занимается трассировкой работы философов.

Аргумент control_ch задает канал, в который должно быть записано сообщение philosopher_done_t после того, как философ съест все, что ему положено. Этот канал затем будет использоваться для определения момента завершения работы всех философов.

Аргументы left_fork и right_fork задают каналы для взаимодействия с вилками. Именно в эти каналы будут отсылаться сообщения take_t и put_t . Но если это каналы, то почему используется тип mbox_t вместо mchain_t ?

Это хороший вопрос! Но ответ на него мы увидим ниже, при обсуждении другого решения. Пока же можно сказать, что mchain — это что-то вроде разновидности mbox-а, поэтому ссылки на mchain-ы можно передавать через объекты mbox_t .

Далее определяется ряд переменных, которые формируют состояние философа:

int meals_eaten{ 0 }; random_pause_generator_t pause_generator; auto self_ch = so_5::create_mchain( control_ch->environment() ); Наверное наиболее важная переменная — это self_ch . Это персональный канал философа, через который философ будет получать ответные сообщения от вилок.

Ну а теперь мы можем перейти к основной логике работы философа. Those. к циклу повторения таких операций как размышления, захват вилок и поглощение пищи.

Можно отметить, что в отличии от решения на базе Акторов, для имитации длительных операций здесь используется this_thread::sleep_for вместо отложенных сообщений.

Попытка взять вилку выглядит практически так же, как и в случае с Акторами:

so_5::send< take_t >( left_fork, self_ch->as_mbox(), philosopher_index ); Здесь используется все тот же тип take_t . Но в нем есть поле типа mbox_t , тогда как self_ch имеет тип mchain_t . Поэтому приходится преобразовывать ссылку на канал в ссылку на почтовый ящик через вызов as_mbox() .

Далее можно увидеть вызов receive() :

so_5::receive( so_5::from( self_ch ).handle_n( 1u ), [&]( so_5::mhood_t<taken_t> ) {...} ); Этот вызов возвращает управление только когда один экземпляр taken_t будет извлечен и обработан. Ну или если канал будет закрыт. В общем, мы здесь ждем поступление нужного нам ответа от вилки.

В общем-то это практически все, что можно было бы рассказать про philosopher_process . Хотя стоит заострить внимание на вложенном вызове receive() для одного и того же канала:

so_5::receive( so_5::from( self_ch ).handle_n( 1u ), [&]( so_5::mhood_t<taken_t> ) { ... so_5::receive( so_5::from( self_ch ).handle_n( 1u ), [&]( so_5::mhood_t<taken_t> ) {...} ); ... } ); Эта вложенность позволяет записать логику работы философа в простом и более-менее компактном виде.

Функция запуска симуляции

При обсуждении решений на базе Акторов мы не останавливались на разборе функций run_simulation() , поскольку там ничего особо интересного или важного не было. Но вот в случае с CSP-подходом на run_simulation() имеет смысл остановиться. В том числе для того, чтобы в очередной раз убедиться в том, насколько непросто писать корректный многопоточный код (кстати говоря вне зависимости от языка программирования).

void run_simulation( so_5::environment_t & env, const names_holder_t & names ) noexcept { const auto table_size = names.size(); const auto join_all = []( std::vector<std::thread> & threads ) { for( auto & t : threads ) t.join(); }; trace_maker_t tracer{ env, names, random_pause_generator_t::trace_step() }; // Создаем вилки. std::vector< so_5::mchain_t > fork_chains; std::vector< std::thread > fork_threads( table_size ); for( std::size_t i{}; i != table_size; ++i ) { // Персональный канал для очередной вилки. fork_chains.emplace_back( so_5::create_mchain(env) ); // Рабочая нить для очередной вилки. fork_threads[ i ] = std::thread{ fork_process, fork_chains.back() }; } // Канал для получения уведомлений от философов. auto control_ch = so_5::create_mchain( env ); // Создаем философов. const auto philosopher_maker = [&](auto index, auto left_fork_idx, auto right_fork_idx) { return std::thread{ philosopher_process, std::ref(tracer), control_ch, index, fork_chains[ left_fork_idx ]->as_mbox(), fork_chains[ right_fork_idx ]->as_mbox(), default_meals_count }; }; std::vector< std::thread > philosopher_threads( table_size ); for( std::size_t i{}; i != table_size - 1u; ++i ) { // Запускаем очередного философа на отдельной нити. philosopher_threads[ i ] = philosopher_maker( i, i, i+1u ); } // Последний философ должен захватывать вилки в обратном порядке. philosopher_threads[ table_size - 1u ] = philosopher_maker( table_size - 1u, table_size - 1u, 0u ); // Ждем пока все философы закончат. so_5::receive( so_5::from( control_ch ).handle_n( table_size ), [&names]( so_5::mhood_t<philosopher_done_t> cmd ) { fmt::print( "{}: done\n", names[ cmd->m_philosopher_index ] ); } ); // Дожидаемся завершения рабочих нитей философов. join_all( philosopher_threads ); // Принудительно закрываем каналы для вилок. for( auto & ch : fork_chains ) so_5::close_drop_content( ch ); // После чего дожидаемся завершения рабочих нитей вилок. join_all( fork_threads ); // Показываем результат. tracer.done(); // И останавливаем SObjectizer. env.stop(); } В принципе, в основном код run_simulation() должен быть более-менее понятен. Поэтому я разберу только некоторые моменты.

Нам требуются рабочие нити для вилок. Этот фрагмент как раз отвечает за их создание:

std::vector< so_5::mchain_t > fork_chains; std::vector< std::thread > fork_threads( table_size ); for( std::size_t i{}; i != table_size; ++i ) { fork_chains.emplace_back( so_5::create_mchain(env) ); fork_threads[ i ] = std::thread{ fork_process, fork_chains.back() }; } При этом нам нужно сохранять и каналы, созданные для вилок, и сами рабочие нити. Каналы потребуются ниже для передачи ссылок на них философам. А рабочие нити потребуются для того, чтобы затем вызвать join для них.

После чего мы создаем рабочие нити для философов и так же собираем рабочие нити в контейнер, т.к. нам нужно будет затем вызывать join :

std::vector< std::thread > philosopher_threads( table_size ); for( std::size_t i{}; i != table_size - 1u; ++i ) { philosopher_threads[ i ] = philosopher_maker( i, i, i+1u ); } philosopher_threads[ table_size - 1u ] = philosopher_maker( table_size - 1u, table_size - 1u, 0u ); Далее мы должны дать философам некоторое время для выполнения симуляции. Дожидаемся момента завершения симуляции с помощью этого фрагмента:

so_5::receive( so_5::from( control_ch ).handle_n( table_size ), [&names]( so_5::mhood_t<philosopher_done_t> cmd ) { fmt::print( "{}: done\n", names[ cmd->m_philosopher_index ] ); } ); Этот вариант receive() возвращает управление только после получения table_size сообщений типа philosopher_done_t .

Ну а после получения всех philosopher_done_t остается выполнить очистку ресурсов.

Делаем join для всех рабочих нитей философов:

join_all( philosopher_threads ); После чего нужно сделать join для всех нитей вилок. Но просто вызывать join нельзя, т.к. тогда мы тупо зависнем. Ведь рабочие нити вилок спят внутри вызовов receive() и никто их не разбудит. Поэтому нам нужно сперва закрыть все каналы для вилок и лишь затем вызывать join :

for( auto & ch : fork_chains ) so_5::close_drop_content( ch ); join_all( fork_threads ); Вот теперь главные операции по очистке ресурсов можно считать законченными.

Несколько слов о noexcept

Надеюсь, что код run_simulation сейчас полностью понятен и я могу попробовать объяснить, почему эта функция помечена как noexcept . Дело в том, что в ней exception-safety не обеспечивается от слова совсем. Поэтому самая лучшая реакция на возникновение исключения в такой тривиальной реализации — это принудительное завершение всего приложения.

Но почему run_simulation не обеспечивает безопасность по отношению к исключениям?

Давайте представим, что мы создаем рабочие нити для вилок и при создании очередной нити у нас выскакивает исключение. Дабы обеспечить хоть какую-нибудь exception-safety нам нужно принудительно завершить те нити, которые уже были запущены. И кто-то может подумать, что для этого достаточно переписать код запуска нитей для вилок следующим образом:

try { for( std::size_t i{}; i != table_size; ++i ) { fork_chains.emplace_back( so_5::create_mchain(env) ); fork_threads[ i ] = std::thread{ fork_process, fork_chains.back() }; } } catch( ... ) { for( std::size_t i{}; i != fork_chains.size(); ++i ) { so_5::close_drop_content( fork_chains[ i ] ); if( fork_threads[ i ].joinable() ) fork_threads[ i ].join(); } throw; } К сожалению, это очевидное и неправильное решение. Since оно окажется бесполезным если исключение возникнет уже после того, как мы создадим все нити для вилок. Поэтому лучше использовать что-то вроде вот такого:

struct fork_threads_stuff_t { std::vector< so_5::mchain_t > m_fork_chains; std::vector< std::thread > m_fork_threads; fork_threads_stuff_t( std::size_t table_size ) : m_fork_threads( table_size ) {} ~fork_threads_stuff_t() { for( std::size_t i{}; i != m_fork_chains.size(); ++i ) { so_5::close_drop_content( m_fork_chains[ i ] ); if( m_fork_threads[ i ].joinable() ) m_fork_threads[ i ].join(); } } void run() { for( std::size_t i{}; i != m_fork_threads.size(); ++i ) { m_fork_chains.emplace_back( so_5::create_mchain(env) ); m_fork_threads[ i ] = std::thread{ fork_process, m_fork_chains.back() }; } } } fork_threads_stuff{ table_size }; // Преаллоцируем нужные ресурсы. fork_threads_stuff.run(); // Создаем каналы и запускаем нити. // Вся нужная очистка произойдет в деструкторе fork_threads_stuff. Ну или можно воспользоваться трюками, которые позволяют выполнять нужный нам код при выходе из скоупа (например, Boost-овским ScopeExit-ом, GSL-овским finally() и им подобным).

Аналогичная проблема существует и с запуском нитей для философов. И решать ее нужно будет подобным образом.

Однако, если поместить весь необходимый код по обеспечению exception-safety в run_simulation() , то код run_simulation() окажется и объемнее, и сложнее в восприятии. Что не есть хорошо для функции, написанной исключительно в демонстрационных целях и не претендующей на продакшен-качество. Поэтому я решил забить на обеспечение exception-safety внутри run_simulation() и пометил функцию как noexcept , что приведет к вызову std::terminate в случае возникновения исключения. ИМХО, для такого рода демонстрационных примеров это вполне себе разумный вариант.

Тем не менее, проблема в том, что нужно иметь соответствующий опыт чтобы понять, какой код по очистке ресурсов будет работать, а какой нет. Неопытный программист может посчитать, что достаточно только вызвать join , хотя на самом деле нужно еще предварительно закрыть каналы перед вызовом join . И такую проблему в коде будет очень непросто выловить.

Простое решение без использования арбитра (официанта)

Теперь мы можем рассмотреть, как в CSP-подходе будет выглядеть простое решение с возвратом вилок при неудачном захвате, но без арбитра.

Исходный код этого решения можно найти здесь .

Нить для вилки

Нить для вилки реализуется функцией fork_process , которая выглядит следующим образом:

void fork_process( so_5::mchain_t fork_ch ) { // Состояние вилки: захвачена или свободна. bool taken = false; // Обрабатываем сообщения пока канал не закроют. so_5::receive( so_5::from( fork_ch ), [&]( so_5::mhood_t<take_t> cmd ) { if( taken ) so_5::send< busy_t >( cmd->m_who ); else { taken = true; so_5::send< taken_t >( cmd->m_who ); } }, [&]( so_5::mhood_t<put_t> ) { if( taken ) taken = false; } ); } Можно увидеть, что эта fork_process проще, чем аналогичная в решении Дейкстры (ту же самую картину мы могли наблюдать, когда рассматривали решения на базе Акторов).

Нить для философа

Нить для философа реализуется функцией philosopher_process , которая оказывается несколько сложнее, чем ее аналог в решении Дейкстры.

void philosopher_process( trace_maker_t & tracer, so_5::mchain_t control_ch, std::size_t philosopher_index, so_5::mbox_t left_fork, so_5::mbox_t right_fork, int meals_count ) { int meals_eaten{ 0 }; // Этот флаг потребуется для трассировки действий философа. thinking_type_t thinking_type{ thinking_type_t::normal }; random_pause_generator_t pause_generator; // Канал для получения ответов от вилок. auto self_ch = so_5::create_mchain( control_ch->environment() ); while( meals_eaten < meals_count ) { tracer.thinking_started( philosopher_index, thinking_type ); // Имитируем размышления приостанавливая нить. std::this_thread::sleep_for( pause_generator.think_pause( thinking_type ) ); // На случай, если захватить вилки не получится. thinking_type = thinking_type_t::hungry; // Пытаемся взять левую вилку. tracer.take_left_attempt( philosopher_index ); so_5::send< take_t >( left_fork, self_ch->as_mbox(), philosopher_index ); // Запрос отправлен, ждем ответа. so_5::receive( so_5::from( self_ch ).handle_n( 1u ), []( so_5::mhood_t<busy_t> ) { /* ничего не нужно делать */ }, [&]( so_5::mhood_t<taken_t> ) { // Левая вилка взята, попробуем взять правую. tracer.take_right_attempt( philosopher_index ); so_5::send< take_t >( right_fork, self_ch->as_mbox(), philosopher_index ); // Запрос отправлен, ждем ответа. so_5::receive( so_5::from( self_ch ).handle_n( 1u ), []( so_5::mhood_t<busy_t> ) { /* ничего не нужно делать */ }, [&]( so_5::mhood_t<taken_t> ) { // У нас обе вилки, можно поесть. tracer.eating_started( philosopher_index ); // Имитируем поглощение пищи приостанавливая нить. std::this_thread::sleep_for( pause_generator.eat_pause() ); // На шаг ближе к финалу. ++meals_eaten; // После еды нужно вернуть правую вилку. so_5::send< put_t >( right_fork ); // Следующий период размышлений должен быть помечен как "normal". thinking_type = thinking_type_t::normal; } ); // Левую вилку нужно вернуть в любом случае. so_5::send< put_t >( left_fork ); } ); } // Уведомляем о завершении работы. tracer.philosopher_done( philosopher_index ); so_5::send< philosopher_done_t >( control_ch, philosopher_index ); } В общем-то код philosopher_process очень похож на код philosopher_process из решения Дейкстры. Но есть два важных отличия.

Во-первых, это переменная thinking_type . Она нужна для того, чтобы формировать правильный след работы философа, а так же для того, чтобы вычислять паузы при имитации "раздумий" философа.

Во-вторых, это обработчики для сообщений busy_t . Мы их можем увидеть при вызове receive() :

so_5::receive( so_5::from( self_ch ).handle_n( 1u ), []( so_5::mhood_t<busy_t> ) { /* ничего не нужно делать */ }, [&]( so_5::mhood_t<taken_t> ) { ... so_5::receive( so_5::from( self_ch ).handle_n( 1u ), []( so_5::mhood_t<busy_t> ) { /* ничего не нужно делать */ }, [&]( so_5::mhood_t<taken_t> ) {...} ); Да, обработчики для busy_t пусты, но это потому, что все необходимые действия либо уже были сделаны перед вызовом receive() , либо будут сделаны после выхода из receive() . Поэтому при получении busy_t ничего не нужно делать. Но сами обработчики должны быть определены, т.к. их присутствие запрещает receive() выбрасывать экземпляры busy_t без обработки. Благодаря присутствию таких обработчиков receive() возвращает управление когда в канал приходит сообщение busy_t .

Решение с официантом и временными отметками

На базе CSP-подхода было сделано еще одно решение, которое я бы хотел здесь кратко осветить. Разбирая решения на базе Акторов речь шла о решениях с арбитром (официантом): мы рассматривали решение waiter_with_queue, в котором официант использует очередь заявок, а так же упоминалось решение waiter_with_timestamps. Оба эти решения использовали один и тот же трюк: официант создавал набор mbox-ов для несуществующих вилок, эти mbox-ы раздавались философам, но сообщения из mbox-ов обрабатывались официантом.

Похожий трюк нужен и в CSP-подходе для того, чтобы я смог переиспользовать уже существующую реализацию philosopher_process из решения no_waiter_simple. Но может ли официант создать набор mchain-ов которые будут использоваться философами и из которых официант будет читать сообщения, адресованные вилкам?

К сожалению, нет.

Создать набор mchain-ов не проблема. Проблема в том, чтобы читать сообщения сразу из нескольких mchain-ов.

В SObjectizer-е есть функция select() , которая позволяет это делать, например, она позволяет написать так:

so_5::select( so_5::from_all(), case_(ch1, one_handler_1, one_handler_2, one_handler_3, ...), case_(ch2, two_handler_1, two_handler_2, two_handler_3, ...), ...); Но для select() нужно, чтобы список каналов и обработчиков сообщений из них был доступен в компайл-тайм. Тогда как в моих решениях задачи "обедающих философов" этот список становится известен только во время исполнения. Поэтому в CSP-подходе нельзя в чистом виде переиспользовать трюк из подхода на базе Акторов.

Но мы можем его переосмыслить.

Итак, суть в том, что в исходных сообщениях take_t и put_t нет поля для хранения индекса вилки. И поэтому нам нужно как-то эти индексы получить. Раз уж мы не можем запихнуть индексы внутрь take_t и put_t , то давайте сделаем расширенные версии этих сообщений:

struct extended_take_t final : public so_5::message_t { const so_5::mbox_t m_who; const std::size_t m_philosopher_index; const std::size_t m_fork_index; extended_take_t( so_5::mbox_t who, std::size_t philosopher_index, std::size_t fork_index ) : m_who{ std::move(who) } , m_philosopher_index{ philosopher_index } , m_fork_index{ fork_index } {} }; struct extended_put_t final : public so_5::message_t { const std::size_t m_fork_index; extended_put_t( std::size_t fork_index ) : m_fork_index{ fork_index } {} }; Вообще говоря, нет надобности наследовать типы сообщений от so_5::message_t , хотя я обычно как раз использую такое наследование (у него есть некоторые небольшие бенефиты). В данном же случае наследование используется просто для того, чтобы продемонстрировать такой способ определения SObjectizer-овских сообщений.Теперь нужно сделать так, чтобы официант читал именно расширенные версии сообщений вместо оригинальных. Значит нам нужно научиться перехватывать сообщения take_t и put_t , преобразовывать их в extended_take_t и extended_put_t , отсылать новые сообщения официанту.

Для этого нам потребуется собственный mbox. Всего лишь :)

class wrapping_mbox_t final : public so_5::extra::mboxes::proxy::simple_t { using base_type_t = so_5::extra::mboxes::proxy::simple_t; // Куда сообщения должны доставляться. const so_5::mbox_t m_target; // Индекс вилки, который должен использоваться в новых сообщениях. const std::size_t m_fork_index; // Типы сообщений для перехвата. static std::type_index original_take_type; static std::type_index original_put_type; public : wrapping_mbox_t( const so_5::mbox_t & target, std::size_t fork_index ) : base_type_t{ target } , m_target{ target } , m_fork_index{ fork_index } {} // Это основной метод so_5::abstract_message_box_t для доставки сообщений. // Переопределяем его для перехвата и преобразования сообщений. void do_deliver_message( const std::type_index & msg_type, const so_5::message_ref_t & message, unsigned int overlimit_reaction_deep ) const override { if( original_take_type == msg_type ) { // Получаем доступ к исходному сообщению. const auto & original_msg = so_5::message_payload_type<::take_t>:: payload_reference( *message ); // Шлем новое сообщение вместо старого. so_5::send< extended_take_t >( m_target, original_msg.m_who, original_msg.m_philosopher_index, m_fork_index ); } else if( original_put_type == msg_type ) { // Шлем новое сообщение вместо старого. so_5::send< extended_put_t >( m_target, m_fork_index ); } else base_type_t::do_deliver_message( msg_type, message, overlimit_reaction_deep ); } // Фабричный метод чтобы было проще создавать wrapping_mbox_t. static auto make( const so_5::mbox_t & target, std::size_t fork_index ) { return so_5::mbox_t{ new wrapping_mbox_t{ target, fork_index } }; } }; std::type_index wrapping_mbox_t::original_take_type{ typeid(::take_t) }; std::type_index wrapping_mbox_t::original_put_type{ typeid(::put_t) }; Здесь использовался самый простой способ создания собственного mbox-а: в сопутствующем проекте so_5_extra есть заготовка, которую можно переиспользовать и сохранить себе кучу времени. Без использования этой заготовки мне пришлось бы наследоваться напрямую от so_5::abstract_message_box_t и реализовывать ряд чистых виртуальных методов.

Как бы то ни было, теперь есть класс wrapping_mbox_t . Так что мы теперь можем создать набор экземпляров этого класса, ссылки на которые и будут раздаваться философам. Философы будут отсылать сообщения в wrapping_mbox, а эти сообщения будут преобразовываться и переадресовываться в единственный mchain официанта. Поэтому функция waiter_process , которая является главной функцией нити официанта, будет иметь вот такой простой вид:

void waiter_process( so_5::mchain_t waiter_ch, details::waiter_logic_t & logic ) { // Получаем и обрабатываем сообщения пока канал не закроют. so_5::receive( so_5::from( waiter_ch ), [&]( so_5::mhood_t<details::extended_take_t> cmd ) { logic.on_take_fork( std::move(cmd) ); }, [&]( so_5::mhood_t<details::extended_put_t> cmd ) { logic.on_put_fork( std::move(cmd) ); } ); } Конечно же, прикладная логика официанта реализована в другом месте и ее код не так прост и короток, но мы не будем туда погружаться. Интересующиеся могут посмотреть код решения waiter_with_timestamps здесь .

Вот сейчас мы можем ответить на вопрос: "Почему каналы для вилок передаются в philosopher_process как mbox-ы?" Это потому, что для решения waiter_with_timestamps был реализован собственный mbox, а не mchain.

Конечно же, можно было бы создать и собственный mchain. Но это потребовало бы несколько больше работы, т.к. в so_5_extra пока нет такой же заготовки для собственных mchain-ов (может быть со временем появится). Так что для экономии времени я просто остановился на mbox-ах вместо mchain-ов.

Conclusion

Вот, пожалуй, и все, что хотелось рассказать про реализованные на базе Акторов и CSP решения. Свою задачу я видел не в том, чтобы сделать максимально эффективные решения. А в том, чтобы показать, как именно они могут выглядеть. Надеюсь, что кому-то это было интересно.

Позволю себе отвлечь внимание тех, кто интересуется SObjectizer-ом. Все идет к тому, что в ближайшее время начнется работа над следующей "большой" версией SObjectizer — веткой 5.6, нарушающей совместимость с веткой 5.5. Желающие сказать свое веское слово по этому поводу, могут сделать это здесь (или здесь ). Более-менее актуальный список того, что поменяется в SO-5.6 можно найти здесь (туда же можно добавить и свои пожелания).

На этом у меня все, большое спасибо всем читателям за потраченное на данную статью время!

Ps. Слово "современные" в заголовке взято в кавычки потому, что в самих решениях нет ничего современного. Разве что за исключением использования кода на C++14.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/437998/